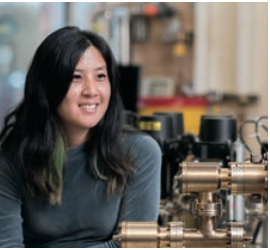

At five-foot flat and just over 100 pounds, Thi Truong is an unlikely weightlifting buff. But the first-year geology Ph.D. student broke California state records

in powerlifting in the bench press and squat, and twice broke the national record for the deadlift when she hoisted an astonishing 287 pounds off the ground — nearly three times her bodyweight.

Initially, Truong was the only lightweight female on the competition circuits she traveled.

“A lot of women are intimidated by learning the basics in a crowded weight room with limited equipment and several men who look more suited to the environment,” she says. “In the beginning, I had to ignore the fact that other people could judge my performance.”

Her philosophy in weightlifting has translated well to academic life, where Truong rarely sees another Asian or woman in geology courses.

“Just like with weightlifting, I learned there is no downside to being someone who doesn’t fit the mold. I can just follow what interests me,” she says.

Truong’s pragmatic outlook on adversity makes sense. A first-generation college student, her parents emigrated from Vietnam in the early 1980s, in the aftershock of the country’s fall to communism. Her father was a military man who fought on the side of the Americans.

“He claims that if he and my mother had stayed in Vietnam, I would not have been able to attend the university, since the government recorded the names of those who fought or provided intelligence to the South Vietnamese. My father’s association with the former enemy could have meant being blacklisted from a public university,” Truong says.

Her parents settled in San Diego, and Truong powered her way through many barriers — with a no-nonsense outlook. Her fierce determination helped her get into the University of California, San Diego, where she earned both an undergraduate and master’s degree in geochemistry. As she moved from undergraduate to graduate work, she was frequently the only woman and the only person of color in field camps, lab work and lecture rooms. But Truong was unfazed.

She approached her petrology lecturer, Professor Pat Castillo, about working in his research group and began studying the origin of mantle plumes. Rock samples from the Juan Fernandez Islands off the coast of Chile allowed her to peer into a distant past using powerful mass spectrometers.

“I think that’s one of the strengths of geology — we have a lot of access to different instruments that can be used to analyze data and explore a single theory,” she muses.

Truong became equal parts scientist and historian, piecing together the ages of Earth from various sources to get a complete story. She also was fascinated with geology forerunners who broke barriers. Her bookshelf holds the biographies of pioneers like Harry Hess, a pillar in plate tectonics theory, and Alfred Wegner, the originator of the theory of continental drift — both scientists who were considered geology giants only

in hindsight.

“It was reassuring to see how different people came to discover the discipline,” she says.

At Oregon State University, Truong is continuing her explorations in geochemisty and geochronology with Professor David Graham. As a first-year graduate student, Truong is just getting started on her research into the volcanic flows of Kauai, one of the northernmost islands of the Hawaiian chain. The island, along with the entire Hawaiian chain, is thought to have originated from a plume of molten rock deep within the Earth’s mantle. Kauai’s older volcanic flows, which date as far back as five million years, offer an opportunity to study the original Hawaiian mantle source. Truong will analyze rock samples to get a more accurate estimate of the trace element compositions and relative ages of volcanic flows on the island. She emphasizes that properly dating the volcano will help researchers understand how and when it formed, as well as predict where the next volcano will appear as the trail continues to spread.

Truong is fortunate to have received an ARCS Foundation scholar award in support of her research. She envisions using the support to attend an international conference, which is an important avenue for developing collaborations.

“I feel a lot of possibility for international collaboration,” she says. “It’s good for a graduate student to have enough money to go to a conference.”

For Truong, geology has provided a fascinating window into the deep past, the interior of the Earth and even the origins of life. In her words, “We can learn a lot about ourselves by knowing what we’re standing on.”

Likewise, Truong has learned a lot about herself by knowing just how much she can lift.