Hello, I’m Sarah Caballero and I’m a 1st year PhD student in Food Science at Oregon State University. This past summer, I road tripped from Southern California, where I grew up and completed my B.S. and M.S. at Cal Poly Pomona. When I applied to OSU, I wanted to work on a project related to food engineering and agricultural sustainability. Soon after admission, I found out that I would be taking lead on the infamous “smoke and wine” project in the College of Agricultural Sciences.

The year of 2020 was one for the books. Working on my master’s degree research under Covid-19 social distancing protocols, I kept glancing nervously out the window in LA County. The skies were a hazy grey, and the day was hot and windy, air that desiccates your mouth as you breathe. Wildfires had crested in Orange County the prior day. I nervously checked social media and kept refreshing the Orange County Wildfire Authority page.

No threat.

No threat.

Then, the winds shifted, and evacuations started. The ‘knock on your door and leave immediately’ style evacuations. I quickly abandoned my experiments in the lab to drive home before any road closures. As the hours passed at home, the atmosphere became saturated with glowing orange smoke. I tried to help my family pack for evacuation but ended up curled up in bed, shaking with fear. Our car loaded and ready to go, sleeping with my shoes by my bed, the winds shifted again during the night. The flames were abated, and life went back to normal.

I did not know it yet, but the seeds for my future PhD project to address threats to agricultural sustainability were just being sown.

While vineyards and wineries suffered insurmountable physical and financial damage during the catastrophic 2020 fires, another silent assailant was just being uncovered. Small, airborne particles, ‘volatile phenols’ released when timber burns, were penetrating the waxy protective layer on grapes close to their harvest time. The grapes’ natural enzymes would then convert these phenols to phenol glycosides; essentially anchoring the volatile compounds into the grape by attaching a sugar molecule. During grape fermentation, these volatiles are released from their glycoside anchors, causing off-flavors and aromas. Wines fermented from grapes exposed to smoke have been described as ‘ashy,’ ‘chemical/plastic,’ ‘tar’ or ‘musty’. Studies have shown that smoke-affected wines negatively impact consumer acceptance of the wine, making these ferments a financial and business risk for wineries. Smoke-exposed grapes may also be left unharvested, as happened during 2020, generating crop loss and food waste.

While the 2024 vintage in the Pacific West and Northwest has spectacular prospects, wildfires are now a regular threat. In the lab, we are working to innovate a protective barrier for wine grapes. Specifically, we are developing a pre-harvest spray coating made of natural fibers that act like an air purification filter. Ideally, smoke compounds will be blocked from absorption into the grape. Then, the coating would be removed during crushing and fermentation.

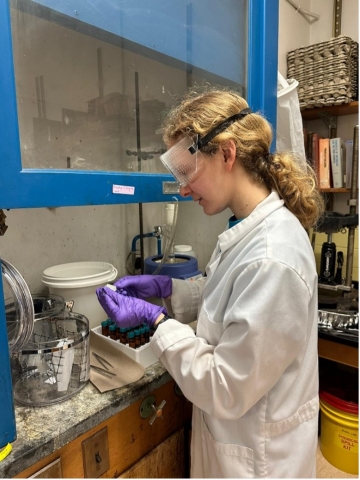

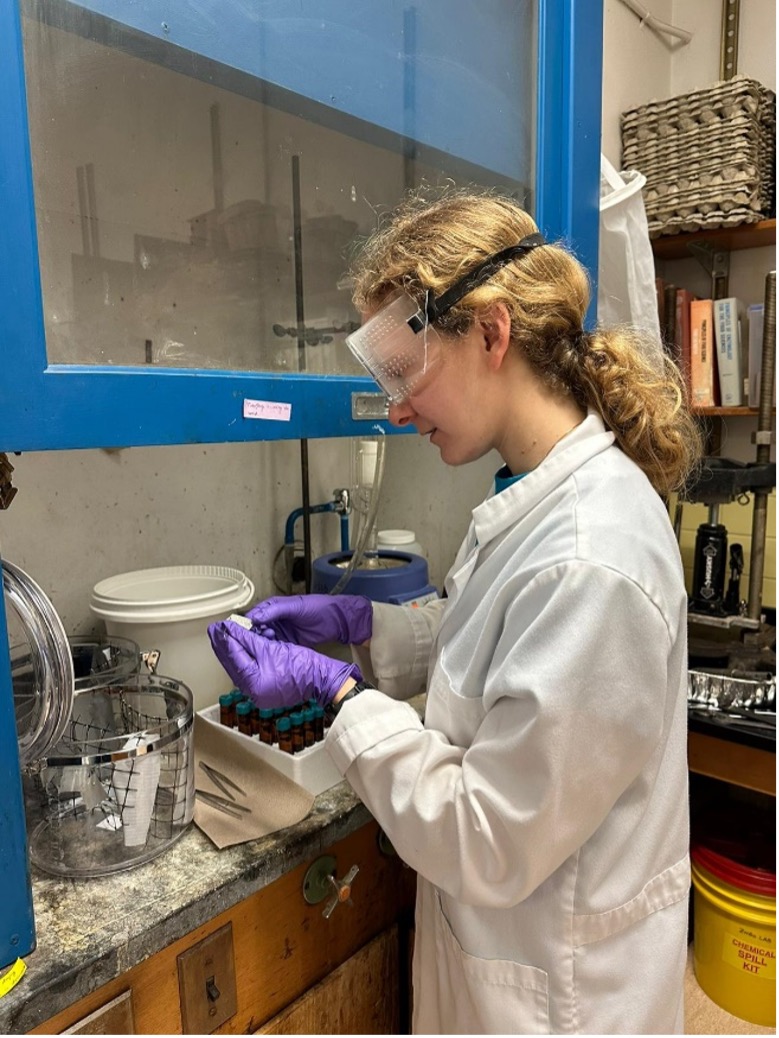

In the lab, I am studying various coating formulations by drying them into films. Then, I hang the films in airtight jars containing smoke compounds (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Inspecting film pieces in the fume hood after exposure to smoke compounds

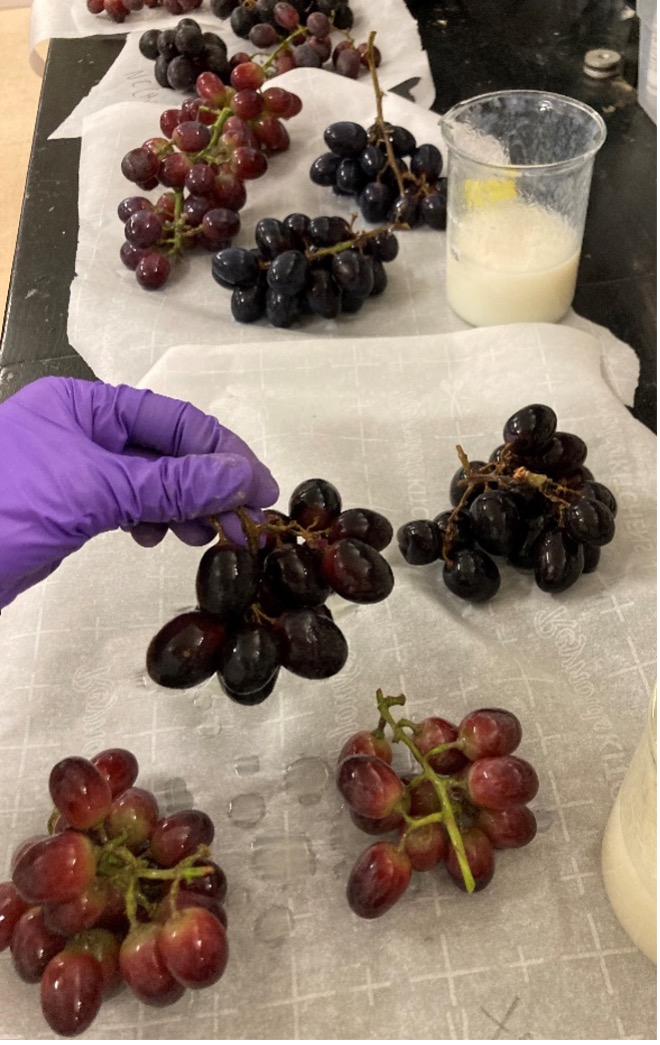

I can measure the amount of smoke compound on the film pieces to determine their effectiveness in blocking the smoke phenols. I have also experimented with putting table grape bunches in these jars and exposing them to smoke (Figure 2). When I open the jars to remove the grapes, a repulsive odor is released. The best way I can describe it is burnt rubber. Due to the unpleasant volatiles, I do my experiments under the fume hood.

Figure 2. Experimenting with dipping table grapes in different coating formulations.

I am reminded of the raw beauty of viticulture when I cycle past vineyards, with trellises lining the green rolling hills, with a blue marbled sky and a misty, forested backdrop (Figure 3). Soon, there will be grapes growing. The ‘burnt rubber’ aroma of smoke compounds is not something that has any place in beautiful grapes or fine wine.

Figure 3. View of a vineyard local to Corvallis from one of my bike rides.

Wildfires can be scary, dangerous, and ominous. My food science research helps ensure that they pose less threat to agriculture, particularly the wine industry. I am excited about the future of this project and about the future of our research in sustainable agriculture.

Please do not hesitate to contact me:

Congratulations Sarah for being the recipient of the Teranishi Graduate Fellowship in Food Chemistry. Check out this LinkedIn post.